WWV's century of service

The WWV time signal service will soon rack up 100 years of broadcasting to the world.

Which technological application has had musical, timekeeping, navigational, scientific, traffic-control, emergency-response and telephone applications? Answer: WWV, one of the world’s oldest continuously operating radio stations.

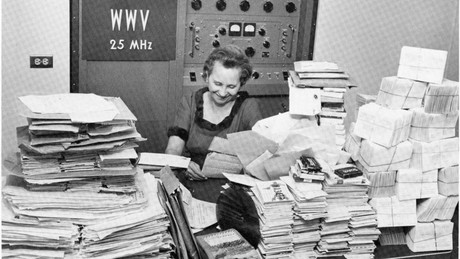

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) received the call letters WWV a century ago, in 1919. Since then, it has operated the station from several different locations — originally Washington, DC, then a succession of locales in Maryland, and now Fort Collins, Colorado.

WWV broadcasts time and frequency information 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to millions of listeners worldwide. The station broadcasts standard time (aka Coordinated Universal Time) at standard frequencies (eg, at 5, 10 and 15 MHz) for use in calibrating radio receivers, as well as alerts of geophysical activity and other information.

WWV broadcasts on six different shortwave frequencies with transmission effectiveness and reception clarity varying depending on many factors, including time of year, time of day, receiver location, solar and geomagnetic activity, weather conditions and antenna type and configuration.

Over the years, WWV has had a startling number of applications.

“Historically, WWV will always be interesting because of the huge role it played in the development of radio in the United States by allowing broadcasters and listeners to check and calibrate their transmit and receive frequencies,” said Michael Lombardi, leader of NIST’s Time and Frequency Services Group.

“Today, WWV still serves as an easily accessible frequency and time reference that provides information not available elsewhere,” Lombardi said. “For example, along with its sister station, WWVH in Hawaii, WWV provides the only high-accuracy voice announcement of the time available by telephone. These phone numbers receive a combined total of more than 1000 calls per day.

“Both the radio and telephone time signals are used by many thousands of citizens to synchronise clocks and watches, and also by numerous industries to calibrate timers and stopwatches,” Lombardi added. “We also know that WWV is highly valued by scientists performing radio propagation studies because it provides them with accurate time markers on six different shortwave frequencies.”

NIST time and frequency broadcasts are also available via the internet, of course, but the internet is not always available. Radio broadcasts can also support celestial navigation and can provide backup communication of public service announcements during disasters or emergencies.

WWV is also popular with amateur radio operators, who use the broadcasts to get geophysical alerts — indicating how far HF radio signals will travel at the current time and receiver location — as well as to tinker with their electronics and teach young people how radio works.

As a ham operator said on US National Public Radio, WWV is “the heartbeat of shortwave radio. When something goes wrong, you check WWV to see if you’re picking up their signal. And you know then that everything’s OK. Maritime operators, military operators, amateur radio operators, we all listen to and use WWV regularly.”

Many technical papers and even books have been written about NIST’s radio work. One such book, published by NIST, is Achievement in Radio.

The radio broadcasting craze started after World War I. NIST, then known as the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), got the call letters WWV for its experimental radio transmitter on 1 October 1919.

A 1919 newspaper story recounted that NBS experimented with broadcasting “music through the air”, transmitting tunes played on a Victrola record player several hundred yards to an NBS auditorium. That demonstration might have been sponsored by military laboratories then operating at NBS.

WWV began broadcasting in May 1920 from Washington, DC, at a frequency of 600 kHz. The first broadcasts were Friday evening music concerts that lasted from 8.30 pm to 11.00 pm. The 50-watt signal could be heard about 40 kilometres away.

Among many other relevant activities, NBS supported the public’s use of the novel technology by publishing instructions on how to build one’s own radio receiver. The agency’s 1922 how-to publication cost 5 cents.

A legacy of impact

WWV and WWVH had a broad impact on the world in their early years, as the 1958 NBS annual report indicated:

The radio broadcast technical services are widely used by scientific, industrial, and government agencies and laboratories as well as by many airlines, steamship companies, the armed services, missile research laboratories and contractors, IGY [International Geophysical Year (PDF)] personnel, satellite tracking stations, schools and universities, numerous individuals, and many foreign countries. They are of importance to all types of radio broadcasting activities such as communications, television, radar, air and ground navigation systems, guided missiles, anti-missile missiles, and ballistic missiles.

NIST has conducted several surveys of WWV users. Many people rely on WWV to set the clocks and watches in their homes, as indicated by regular increases in calls to the telephone time-of-day service whenever daylight saving time starts or ends.

In one interesting example of the NIST radio station’s impact, WWV time codes were used in a 1988 project by the city of Los Angeles to synchronise traffic lights at more than 1000 intersections. City officials estimated that this project saved motorists 55,000 hours a day in driving time, conserved 83 million litres of per year in fuel and prevented 6000 to 7000 tonnes of pollutants per year.

“It’s not easy to think of a lot of technical services offered by the government that have stayed relevant for 100 years, but WWV is about to do just that,” Lombardi said.

Originally published here.

ARCIA update: engaging with industry in 2026

ARCIA is encouraging the radio and critical communications industries to participate in a...

RFUANZ report: welcome to 2026

There has been plenty going on with RFUANZ recently — here are a few of the key things that...

2025–26 Thought Leaders: Tim Karamitos

Tim Karamitos from Ericsson discusses the connectivity requirements of emergency services and...